Alaska Tick Surveillance Results

The geographic range of many tick species is changing due to changes in climate, how we use land, or due to movement of people and animals. Rapid ecological change in the state has raised the concern regarding the emergence of vector-borne diseases that could affect public and wildlife health. The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG), and the University of Alaska-Anchorage Institute for Circumpolar Health Studies (ICHS) are working together to track ticks in the state through the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program. The 2019 Alaska Submit-A-Tick Report summarizes the most recent information from these efforts.

2019 Results

Main Findings in 2019

- In 2019, there were 232 records collected representing 522 individual ticks. The number of tick records in 2019 was more than double the number collected in the previous year, likely reflecting the increase in awareness of ticks and the program.

- The majority of ticks (45.8%) submitted were Ixodes angustus.

- Of the 232 tick records in 2019, most were found on animals (41% on domestic animals and 44% on wildlife). Other submitted ticks were found on humans (9%) and in the environment (7%).

- The largest number of records were from May-August, peaking in July.

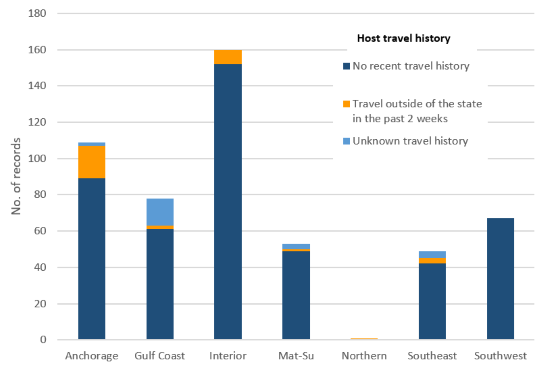

- Ticks were received from all six Alaska Public Health Regions in 2019 with most ticks from the Interior region (n=160, 31%), Anchorage (n=109, 21%), the Gulf Coast (n=78, 15%), and Southwest (n=67, 13%).

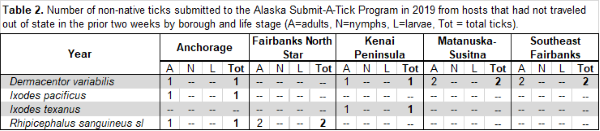

- In 2019, 11 non-native ticks were submitted from hosts without recent travel history. No tick species met the criteria for establishment in any borough.

- Active surveillance in Anchorage, including tick drags and small mammal trapping yielded two adult I. angustus.

What These Results Mean for Alaskans

While the risk of tick bites and acquiring a tick-borne disease in Alaska remains low, new tick species may be arriving and establishing in the state. Monitoring tick distributions through the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program will likely be the most resource-effective method for collecting and disseminating up-to-date information to clinicians, veterinarians, and the public. Alaskans should become familiar with identifying ticks, and clinicians and veterinarians should review common tick-borne disease symptoms. Continue to take precautions to avoid tick bites when traveling to tick endemic areas outside of Alaska, and do tick checks on yourself and your pets before traveling back to Alaska. Biologists who spend time in the field in the summer should also check for ticks on themselves at the end of each field day, particularly if handling wildlife regularly. Please turn in all ticks to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation through the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program.

2019 Results

Tick Species

In 2019, there were 232 records representing 522 individual ticks (Table 1)1. Non-native ticks (including Amblyomma americanum, Dermacentor andersoni, D. variabilis, Ixodes pacificus, I. ricinus, I. scapularis, I. texanus, and Rhipicephalus sanguineus) accounted for 15% (n=34) of the records. In the first year of the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program, we received specimens of 13 tick species. The majority of tick records were submitted by the public (n=123, 53%) followed by biologists (n=68, 29%), and veterinarians (n=37, 16%). Human health professionals submitted 4 records (2%).

Table 1. Number of Ticks Recorded in Alaska in 2019

| Species | Total Ticks |

|---|---|

| Tick species with historical presence records in Alaska | |

| Haemaphysalis leporispalustris | 142 |

| Ixodes angustus | 239 |

| Ixodes auritulus | 1 |

| Ixodes signatus | 11 |

| Ixodes uriae | 84 |

| Non-native tick species | |

| Amblyomma americanum | 12 |

| Dermacentor andersoni | 3 |

| Dermacentor variabilis | 12 |

| Ixodes pacificus | 2 |

| Ixodes ricinus | 1 |

| Ixodes scapularis | 8 |

| Ixodes texanus | 4 |

| Rhipicephalus sanguineus | 3 |

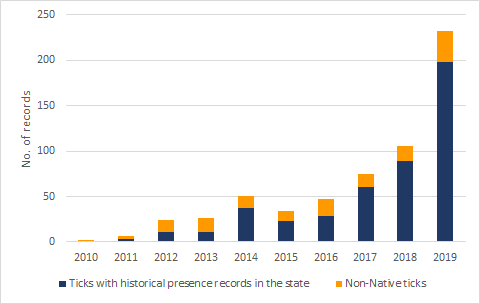

The total number of tick records collected each year has increased over the past 10 years, with the largest increases in the records of tick species that have historically been present in the state (Figure 1). Much of this increase is likely due to increased awareness of ticks and promotion of the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program.

1These numbers include ticks submitted from both JBER and UAA tick drags and small mammal trapping.

Figure 1. Number of Tick Records Collected in Alaska from 2010-2019

Host Information

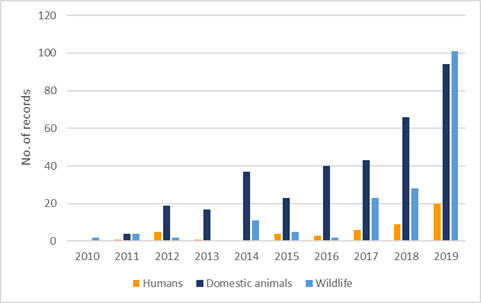

In 2019, the most common host for reported ticks was domestic animals (n=94 records, 41%) followed by small wild mammals (n=77 records, 33%), wild birds (n=24 records, 10%), and humans (n=20 records, 9%). A small number of ticks were found off of a host in the environment (n=16 records, 7%) in places like a bed or in nesting materials of bird colonies. Only one record was missing host information.

Over the past 10 years, the number of ticks submission from domestic animals and wildlife has increased the most substantially (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Submissions by Host

Seasonality and Travel History of Hosts for Submitted Ticks

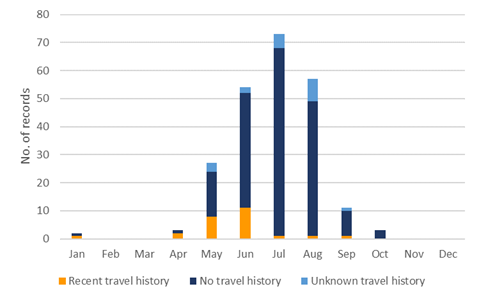

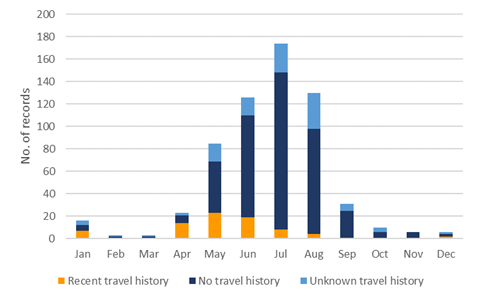

In 2019, most ticks were submitted between May and September, with a distinct peak in June—August (Figure 3). The peak of travel-related tick submissions was slightly earlier in the year compared to overall tick submissions. Travel-related tick submissions occurred in most months except February, March, November, and December with the largest number of submissions in May—August. These trends were similar to the trends in submissions between 2010 and 2019.

Figure 3. Seasonality of Tick Submissions from People or Pets that had Recently Traveled Out of Alaska in a) 2019 and b) 2010-2019

a) 2019

b) 2010-2019

Tick Submissions by Geographic Region

The Alaska Submit-A-Tick program received ticks from all six Alaska Public Health Regions in 2019 (Figure 4). While the largest percentage of found ticks came from the Interior Region (n=160, 31%), the program received substantial numbers of ticks from other regions, including Anchorage (n=109, 21%), the Gulf Coast (n=78, 15%), and Southwest (n=67, 13%). A similar amount of ticks were found in the Southeast Region (n=49, 9%) and Mat-Su (n=53, 10%). Only one tick was found in the Northern Region of Alaska.

Figure 4. Tick Submissions by Alaska Public Health Regions

Evaluation of Establishment Criteria

In order to be considered established and reproducing locally, two or more life stages or 6 individuals of a particular tick species need to be found in a borough in a single year from a host without travel history outside of the state in the prior two weeks. In 2019, 11 non-native ticks were submitted from hosts without recent travel history (Table 2). No tick species met the criteria for establishment in any borough.

Table 2. Number of Non-Native Ticks Submitted to the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program in 2019 from Hosts That Had Not Traveled Out of State in the Prior Two Weeks by Borough and Life State (A=Adults, N=Nymphs, L=Larvae, Tot=Total Ticks)

Summary of Alaska Tick Surveillance Results 2010-2022

Findings from the Alaska Submit-A-Tick Program and active tick surveillance efforts from 2010 through 2022 are summarized in the State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin: Ticks as a Potential Public Health Concern in Alaska, 2010-2022. This bulletin was contributed by Dr. Micah Hahn (Insitute for Circumpolar Health Studies, University of Alaska Anchorage) and published on June 14, 2023.

Alaska Tick Publications

The publications listed below were authored by members of our team and highlight the findings of tick studies in Alaska. For additional information about these studies, contact Dr. Micah Hahn (Insitute for Circumpolar Health Studies, University of Alaska Anchorage).

Indicates an external site.

Indicates an external site.