Alaska’s Water Quality Standards, Assessment, and Restoration Program Annual Highlights 2019

Last Updated: March 2020

Table of Contents

- Small Streams Survey

- Anchor River Restoration

- Mapping Aquatic Priorities

- Kenai River Monitoring

- Clean Vessels Outreach

- Ketchikan Beaches Update

- Harmful Algal Blooms

- Fairbanks Green Infrastructure

- What is Green Infrastructure?

- Chena River Improvement

- Zinc, Stormwater, & Salmon

- Community Watershed Planning

- Water Sample Collection Tips

- Looking Ahead to 2020

- Contacts

Download the Annual Highlights 2019 as PDF file

Small Streams Survey (Southeast)

By Morgan Brown

Alaska, which is home to more than 40% of the nation’s surface waters, has tens of thousands of small streams and creeks that trap flood waters, filter pollutants, recycle nutrients, provide fish and wildlife habitat, recharge groundwater, and are important in maintaining quality and supply of drinking water. The health of these small streams is critical to the integrity of downstream rivers and waters that they feed.

In order to maintain the integrity of Alaska’s waters, we must first know what their baseline water quality conditions are. These conditions can be measured in terms of water chemistry (e.g., dissolved oxygen, pH, metals concentrations), biological characteristics (e.g., invertebrates or bugs living in the water), and physical characteristics (e.g., flow, fish cover). Funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Alaska’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has been conducting baseline water quality monitoring surveys in various types of waterbodies since 2002, including three streams surveys in different regions of the state. By understanding baseline conditions, we can characterize the state of Alaska’s waters and understand changes over time.

During summer 2019, DEC and partners* surveyed 38 streams in southeast Alaska from Yakutat to Prince of Wales Island. Streams were categorized into small and medium size classes and chosen randomly. (Large streams, or rivers were sampled in 2018 during the Southeast Rivers Survey.) Crews from DEC and the UAA Alaska Center for Conservation Science accessed field sites by road, float plane, or helicopter. Once onsite, crews worked downstream to upstream of a reach proportional to the width of the stream collecting samples and data from 10 evenly-spaced transects along the reach.

During summer 2019, DEC and partners* surveyed 38 streams in southeast Alaska from Yakutat to Prince of Wales Island. Streams were categorized into small and medium size classes and chosen randomly. (Large streams, or rivers were sampled in 2018 during the Southeast Rivers Survey.) Crews from DEC and the UAA Alaska Center for Conservation Science accessed field sites by road, float plane, or helicopter. Once onsite, crews worked downstream to upstream of a reach proportional to the width of the stream collecting samples and data from 10 evenly-spaced transects along the reach.

DEC’s stream survey crew summer 2019.

This summer was unique relative to past sampling seasons. The period of July 17, 2018 – October 8, 2019 saw the longest duration of drought in Alaska (65 weeks), and southeast Alaska experienced Extreme Drought conditions for the first time ever recorded. While a handful of sites are dropped in the field each survey (often because they are unsafe to access), summer 2019 saw a whopping 35 sites dropped. Furthermore, even within sampled sites, flow was often too low to be measured. While these conditions are unusual, randomized surveys are designed to capture natural variation, and this highlights the importance of gathering a large volume of information over a long period of time. Data collected from this survey will be added to DEC’s water quality database and used to characterize the health of Southeast Alaska streams. Now and in the future, this information will provide valuable insights about Alaska’s waters.

*ADEC 2019 Partners: US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA), US Forest Service (USFS, Tongass NF), Alaska Department of Natural Resources (ADNR)

Anchor River Restoration (Kenai Peninsula)

By Sarah Apsens

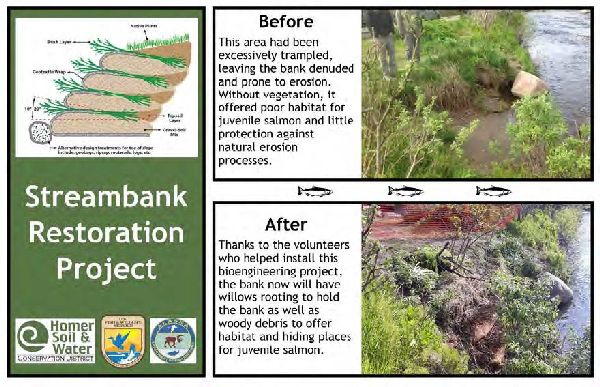

The Homer Soil and Water Conservation District (HSWCD), supported with funds from a DEC Alaska Clean Water Action (ACWA) grant, completed a restoration project at a popular Anchor River State Recreation Area. The riverbank near the Silverking campground had been trampled after many years of use. Trampled streambanks are more prone to erosion, which can cause water quality problems, and are less than ideal habitat for juvenile salmon. To restore the site, HSWCD carried out a site survey, consulted with residents of Anchor Point and partner organizations, and formulated a restoration plan. Community meetings and social media were used to keep the public up to date on restoration activities.

In June 2019 members of the community were invited to participate in a hands-on streambank revegetation workshop. Bioengineering techniques were demonstrated and the importance of streambank habitat for juvenile salmon were discussed. Two sites totaling approximately 30 feet in length were restored using coir logs, brush layering, spruce tree revetment, and vegetation mats. Informational signage was posted at the sites. Alaska State Parks is planning on building off the work done by HSWCD at the site in the near future. HSWCD uploaded an extensive video library of the entire restoration process to YouTube. Links to the videos are in the final report for this project Anchor River Streambank Restoration and can be found on DEC’s water quality reports webpage.

See social media posts on the “Anchor River Updates” Facebook Page

Below is an example of the informational signage posted at the restoration site:

Mapping Aquatic Priorities in Interior Alaska (Interior)

By Chandra McGee

DEC is participating in a community workgroup to produce mapping tools for permitting and land management agencies. The mapping tools will help agencies to protect and improve watershed habitats for fish and wildlife and water quality.

The goals of the workgroup are to:

- Identify and prioritize specific areas for preservation and restoration

- Identify key areas for compensatory mitigation

- Identify sites to restore, establish, enhance and preserve Chinook Salmon and other aquatic resources

- Gather and review existing plans, reports, current conditions, threats and future trends

- Map these areas in a comprehensive GIS map

To develop the mapping tool, a diverse group of scientists, land and resource management and regulatory agency personnel, conservation organizations and business interest groups were invited to multiple workshops to discuss aquatic resources in each watershed, including available data, historic information, and future threats.

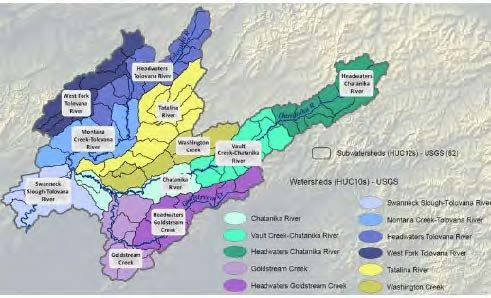

In 2017-2018 a GIS map was developed for the Chena River watershed. In 2018-2019, the same process was applied to the Tolovana River watershed. Beginning in 2020, the group plans to begin work on the Salcha River watershed.

As part of the map development, watershed resource action plans were also developed for each watershed. The plans include objectives and action items for protecting and restoring aquatic resources.

For more information, and for copies of the mapping tools, visit Escape Wrap.

Sub-watersheds of the Tolovana River.

Kenai River Water Quality Monitoring (Kenai Peninsula)

Soldotna Creek monitoring location (Photo source: KWF).

By Sarah Apsens

This past summer DEC helped fund an effort by the Kenai Watershed Forum (KWF) to monitor potential sources of stormwater in the Kenai River watershed. Untreated stormwater can contain metals that are harmful to aquatic organisms.

This monitoring effort was done to supplement the annual multi-agency baseline study organized by KWF. Water quality data has been collected since the early 2000’s as part of the baseline study. Water quality samples are collected at 22 different main stem sites along the Kenai River in spring and summer. DEC has participated in the multi-agency baseline study for several years.

The information collected provides valuable information on past and current trends in water quality in the Kenai River.

Clean Vessels Grant Outreach (Statewide)

By Laura Eldred

Velkommen! That’s what we heard in May when the DEC’s Clean Vessels program headed to Petersburg, AK for the Little Norway Festival. Petersburg is on Mitkof Island in southeast Alaska and is one of Alaska’s major fishing communities. Petersburg also has a Norwegian heritage and is known by some as Alaska’s Little Norway.

Alaska has over 90,000 registered recreational motor boaters, many of whom need to manage the sewage waste from their boats. Unfortunately, many Alaskan boaters are not aware of the need to use sewage pump-out stations or how to properly treat marine sewage discharges. In addition, many harbors lack pump-out systems, or the current infrastructure is not user friendly or convenient.

In response to this need, DEC’s Nonpoint Source section worked with partners (such as the Marine Exchange of Alaska) to implement an education and outreach campaign across coastal Alaska, using grant funds from the Coastal Clean Vessel Act program from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. The goal of the outreach program was to improve water quality in inland waters and harbors by reducing sewage pollution.

Harbor in Petersburg, AK.

DEC and Marine Exchange staff participated in the Little Norway Festival parade in Petersburg to share information on clean harbors and clean boating practices.

A number of successful outreach activities occurred in 2019 including the multi-day festival in Petersburg. All events included information on how boaters can help protect water quality with clean boating tips. For interested boaters, we provided sewage pump-out “kits” that included a quick-connect mechanism for connecting to a sewage pump-out station and various useful items like gloves, absorbent pads and hand sanitizer.

More information about Alaska Clean Harbors

Ketchikan Beaches Update (Southeast)

By Gretchen Augat

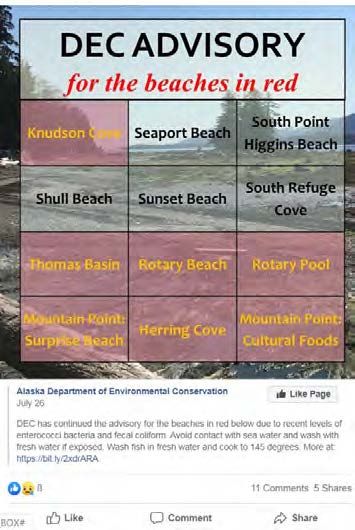

The Alaska Beach program began monitoring fecal waste contamination along the Ketchikan coastline waters in 2017. Marine water has been collected during three recreational seasons at 13 beaches to evaluate potential health risks, and to notify the public when levels exceeded Alaska water quality standards.

Fecal coliform bacteria and enterococci testing has shown that marine water at 11 of the 13 beach monitoring sites has failed to meet the state standards for two or more years during this study. A specialized bacteria genetic identification, called microbial source tracking, was also performed where the human host marker was detected at all 13 monitoring locations, the dog host marker discovered at 12 locations, and the gull host marker found at 11 locations.

Numerous potential bacteria sources are present along the Ketchikan coast, including: private and public sewer treatment system outfalls, public sewer treatment system emergency bypass discharges, sewer line breaks, individual septic tanks, wildlife, pet feces, boats in harbor and launch areas, and private watercraft, ferries, and cruise ships.

Example Facebook post from July 2019 highlighting beaches with recreational advisories.

View the comprehensive monitoring reports (2017, 2017-2019 pending) and a field report (2018).

What’s next for Ketchikan beaches?

Given the numerous potential bacteria sources to the coastal beaches, several sources may be contributing to the elevated bacteria levels at each location, with influence from air and water temperature and precipitation. Bacteria beach monitoring, and potentially modeling, is planned for the 2020 recreational season. In addition, a Watershed Management Plan is being developed to encompass the entire Ketchikan area, and will evaluate management options to reduce bacteria entering Ketchikan freshwater watersheds and coastal marine waters. This plan, being developed in collaboration with tribal, local, and state governments and the Ketchikan community, has draft and final versions scheduled for completion in September 2020 and February 2021, respectively.

Want the latest beach updates? Check out these ways to stay informed:

- DEC Facebook page

- Ketchikan Events Facebook page

- Alaska Beach Program website

- DEC Press Releases

- Public meetings in Ketchikan throughout the year

- Advisory signs posted at affected beaches

- Weekly stakeholder email updates (contact Gretchen Augat to sign-up)

It’s Not Easy Being Green... Algae (Statewide)

By Brock Tabor

In certain parts of the lower 48 people casually use the term harmful algal bloom or ‘HAB’ when considering where to go swimming or take their pets to cool off. Here in Alaska, we also use the term HAB but are more likely to associate it with potential negative health effects from eating shellfish (don’t clam during months without an ‘r’).

Freshwater HABs

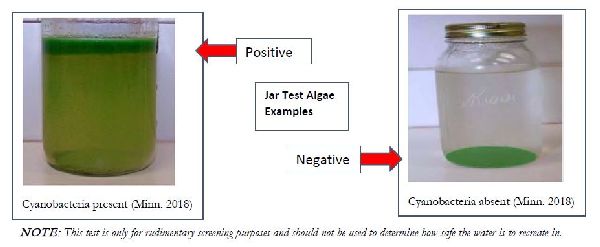

Cyanobacteria are an important, natural component of Alaska freshwater lakes, rivers, and streams and are also present in home aquariums and the soil in residential lawns and indoor potted plants. Under certain conditions cyanobacteria populations can rapidly increase to levels that interfere with the recreation and domestic beneficial uses (i.e. drinking water) of a water body. This rapid increase is often referred to as a harmful cynanobacteria bloom or harmful algal bloom (HAB).

HABs often have variable appearance in the form of foam, scum, or mats on the surface of water - especially near shorelines. Dense blooms near the surface may resemble a layer of green paint or spilled milk. Blooms occur in the warmer months and can be more frequent in times of drought, and as the number of algal cells increase, the chances for toxins also increase. Nontoxic algae and floating plants can be distinguished from cyanobacteria blooms by color and texture. Green algae commonly encountered are typically are grass-green in color (see comparison images below). Many types of green algae consist of long, stringy filaments that feel either slippery or like cotton.

A variety of factors can influence the formation of an HAB including light availability, increases in air and water temperatures (e.g., waters above 25°C (USGS 2015)), increases in nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous, and how quickly water ‘flushes’ or moves through a waterbody.

Marine HABs

Marine HABs are generally associated with the phytoplankton species Alexandrium (paralytic shellfish poisoning in humans), Pseudo-nitzschia (amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans, also called domoic acid poisoning), and Dinophysis (diarrhetic shellfish poisoning in humans) although cyanobacteria can be present as well. When filter feeders such as zooplankton, clams, oysters, mussels, and small fish eat the algae, they accumulate algal toxins in their tissues. The toxins are passed up the food chain to higher level predators such as fish, birds, marine mammals, and humans as they consume the contaminated organisms. Marine HABs are especially disconcerting as they threaten health and impose significant costs on coastal communities. Commercial shellfish harvesting programs are required to conduct testing and monitoring and recreational or personal use harvesting must rely on potentially dated information regarding how ‘safe’ it is to harvest.

What is DEC doing?

The DEC Environmental Health (DEC-EH) program actively facilitates the testing and monitoring of the commercial shellfish industry. DEC is also an active participant on the Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network which focuses on marine HABs. The network is composed of federal, state, tribal, and university experts in toxicology and marine biology in an effort to raise HAB awareness, research, monitoring, and response to marine HABs.

DEC currently has limited reports of freshwater HABs and is providing information to the general public to help increase awareness about the potential health hazards associated with contact.

Note: This test is only for rudimentary screening purposes and should not be used to determine how safe the water is to recreate in.

The most common ways to come into contact with freshwater HABs are:

- Drinking/Swallowing – Accidental or incidental drinking of HABs-contaminated water can occur during water-related recreational activities

- Skin Contact – Swimming, fishing, waterskiing, tubing and other recreational activities in HABs-contaminated waters

- Inhaling – Breathing aerosolized water droplets (misting) of HABs-contaminated water from recreational activities such as jet-skiing or power boating

Symptoms of exposure to algal toxins include rashes, hives, diarrhea, vomiting, coughing, or wheezing. Boiling the water or use of ‘camping’ water purifiers will not make the water safe for drinking.

If you or your pet comes into contact with water you suspect may have a HAB, rinsing exposed skin and items with uncontaminated water as soon as possible is recommended, especially for items that may go into the mouths of infants and children under the age of six years (i.e., teething rings, nipples, bottles, toys, silverware). Likewise, if you plan to eat fish caught from waters suspected of having a HAB, rinse all fish parts well in tap water before cooking and eating. All fish processing surfaces should be washed thoroughly with soapy water.

Do not drink or allow your pet to drink from water suspected of having a HAB.

What is Green Infrastructure?

Green infrastructure (GI) is an approach to water management that protects, restores, or mimics the natural water cycle. While single purpose gray infrastructure, such as conventional piped drainage and water treatment systems, is designed to move runoff away from the built environment, GI reduces and treats runoff at its source. GI incorporates both the natural environment and engineered systems to provide clean water, conserve ecosystem values and functions, and provides a wide array of benefits to people and wildlife. Examples of GI includes vegetated swales, rain gardens, retention areas, constructed wetlands, permeable pavers, tree wells and planters, and re-vegetation/rehabilitation efforts.

The image above is a flow-through planter box at S Salon in Fairbanks, Alaska. This example uses a green infrastructure technique to capture and treat roof runoff water. The planter box is installed on top of permeable pavers to allow water infiltration to the ground. Photo courtesy of the Tanana Valley Watershed Association.

Fairbanks Green Infrastructure Group (Interior)

By Chandra McGee

The Fairbanks Green Infrastructure Group (AKA “GIG”) promotes green infrastructure projects and planning in Fairbanks. Contact Chandra McGee for more information about GIG or to be added to their mailing list.

Who? GIG is composed of a diverse group of partners that share the common goal of a healthy watershed. Current members include representatives from DEC, non-profits, local, state and federal agencies, as well as small business owners and members of the public.

What? GIG works to renew a cleaner and healthier watershed by making green infrastructure a common practice for home and business owners in the greater Fairbanks area. Through community support and involvement, GIG promotes sustainable use of our natural environment for the benefit of present and future generations.

How? GIG works to implement small and large scale green infrastructure projects, engage the community, and influence future development.

History: In 2010 the City of Fairbanks and partners received funding from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources to create a Green Infrastructure Guide for Homeowners in Fairbanks. In 2011, DEC convened the first meeting of the group to collaborate to secure additional funding for green infrastructure projects, share resources, and work on the common goal of increasing the amount of GI in Fairbanks. Since its inception, the group has worked to obtain funding and implement numerous on the ground projects around Fairbanks, support planning efforts such as the Green Streets Policy, and produced two green infrastructure guidance documents.

Permeable paver installation at the Georgeson Botanical Garden in Fairbanks.

Chena River Watershed Water Quality Improvement! (Interior)

By Amber Bethe

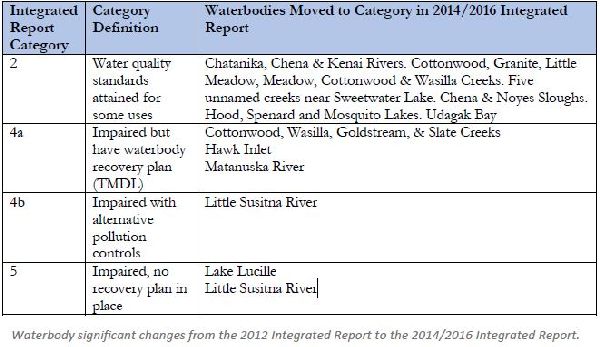

As a requirement of the Clean Water Act, every two years DEC reports on the condition of Alaska’s waters through the Integrated Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment Report (Integrated Report). Each report documents changes in waterbody condition from the previous report, for example if a previously polluted waterbody is now healthy. In November 2018 DEC released the combined 2014/2016 Integrated Report, which removed several waterbodies in the Fairbanks area from the impaired waters list. The Chena River, Chena Slough and Noyes slough were previously listed as impaired (polluted) from petroleum hydrocarbons, oil and grease, and for sediment in the 1990s. Noyes Slough was also listed as polluted from residues (debris or trash).

Since the listings, partnerships and community involvement have spurred water quality improvements in the watershed. Community cleanups, habitat restoration, green infrastructure development, best management practices to control stormwater, and replacement or removal of culverts have all contributed to reductions in sediment, hydrocarbons and residues. In 2010 the petroleum hydrocarbons impairment was removed from the Chena River. Data collected in 2011-2012 showed that sediment levels met water quality standards, allowing DEC to remove all three waterbodies from the 2014/2016 list of impaired waters for sediment.

Many thanks to all the partners and organizations who helped to improve water quality in these waterways!

View current information about the Integrated Report, and view more information about the Chena River Success Story.

Zinc, Stormwater, and Salmon (Statewide)

By Sarah Apsens

What is zinc? Zinc (Zn) is a common metal used in a wide array of manufacturing processes. Zinc is also found naturally in food and in our bodies. Our immune system uses zinc and so does our sense of smell and taste. However, too much exposure to zinc can be detrimental to health. Aquatic organisms like fish are especially sensitive to increases in metals like zinc, and excess zinc can seriously impact aquatic ecosystems. DEC has measured increases in zinc in some of Alaska’s waterways in recent years. The observed increase is likely from polluted runoff in a watershed, and not from natural sources. Understanding where zinc comes from and how to mitigate it is key in protecting Alaska’s waterways.

Where does zinc come from? Zinc’s properties make it a popular additive for an array of manufacturing, construction, and automotive products. Zinc is used to galvanize metal, so it is found in storm drain pipes, corrugated metals, and chain link fencing. Zinc is most commonly found in homes and businesses in roofing material and drainage pipes. Household products like fertilizers, fungicides, and pesticides contain zinc. Automobile tires, motor oil, and lubricants are a known source of zinc. Some batteries contain zinc. Zinc is naturally found in some rocks, though these rocks are usually found deep underground. Drainage from abandoned mines is a source of zinc in some areas in the western United States. Zinc levels in waterways can increase for a short time following forest fires.

How does zinc enter waterways? Zinc and copper enter waterways most commonly through storm water runoff. Zinc is easily entrained by water as zinc compounds are soluble in water. Particles from vehicle tires, brake pads, and motor oil build up on road surfaces with regular use. During rain events water washes over roads and transports zinc particles to waterways. Zinc can also enter waterways by leaching from galvanized metal surfaces.

Why do care about zinc in waterways? Impacts of zinc and stormwater runoff on salmonids (the family of fish that includes salmon and trout) include damage to gills and increased mortality. Copper, also commonly found in stormwater along with zinc, can impact salmon’s sense of smell which they use to navigate to natal streams. Zinc in combination with copper or other stormwater runoff is often more toxic than zinc alone.

What can we do to reduce zinc? Installing and maintaining green infrastructure can greatly reduce zinc and other contaminants from entering waterways. In one study, simple filtering of contaminated storm water through plant covered soil reduced Coho salmon mortality by 100%. Homeowners can help protect waterways from excess zinc by cleaning up small oil spills in driveways and keeping cars and other vehicles well maintained. Homeowners and businesses can adopt a more conservative use of lawn care products. Owners of waterfront property can maintain and protect riparian buffers on their property.

Working with Communities on Watershed Planning (Statewide)

By Gretchen Augat

DEC’s Alaska Clean Water Actions Grants Program is funding Watershed Management Plans for the urban watersheds in Ketchikan, the Jordan Creek watershed in Juneau, and for Lake Lucile in Wasilla. The plans are designed to understand the current pollution sources and determine actions to take to improve or protect water quality. Wastewater and stormwater management options are explored to reduce the pollutants (mainly bacteria in Ketchikan and stormwater in Juneau) from entering freshwater and coastal marine waters. Lake Lucile is focused on finding ways to reduce stormwater pollutants from being discharged to the lake.

Watershed Management Plans are developed by working directly with tribal, local, and state governments and the community. There are six steps to watershed planning, and nine elements to a successful plan (see below). Feel free to contact DEC if you’d like more information on these watershed planning projects or would like to start your own watershed planning process.

Tips When Collecting Water Quality Samples (Statewide)

By John Clark

What is a Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP)?

A QAPP is the guiding document of water quality sampling. It describes who, what, when, where, why, and how water sampling is going to occur along with other technical quality assurance and quality control measures. A QAPP is required for any water monitoring project funded using EPA pass-through monies such as the Alaska Clean Water Action grants. Permitted facilities that have a monitoring requirement as part of the permit conditions may also need a QAPP. The DEC Quality Assurance Officer approves QAPPs for DEC projects.

What are some things to keep in mind when conducting water quality sampling?

- Make sure the calibration solutions are not expired by keeping a log with expiration dates and checking the dates before calibrating the equipment.

- When making a correction in the field data sheet or notebook, make sure the change is properly documented and dated.

- When collecting water samples, it is important the method used matches what was approved in the QAPP.

- For samples that require preservation, is it being done in accordance with the sample method directions?

- Did you fill out a chain-of-custody form? A chain-of-custody is an unbroken trail of accountability that ensures the physical security of samples, data, and records.

- Did you check to make sure the samples were received by the laboratory within the holding time limit and temperature? It is critical to not falsify or disguise any of this information. Remember to use a clean hands/dirty hands procedure when collecting certain types of samples (i.e. bacteria, hydrocarbons). One member of the two-person sampling team is designated as "dirty hands"; the second member is designated as "clean hands." All operations involving contact with the sample bottle and transfer of the sample from the sample collection device to the sample bottle are handled by the individual designated as "clean hands." "Dirty hands" is responsible for preparation of the sampler (except the sample container itself), operation of any machinery, and for all other activities that do not involve direct contact with the sample.

By having an approved QAPP in place and following good sample collection practices, it increases the confidence level that the sampling results are valid and will be useable by DEC and others to make informed water quality decisions.

Looking Ahead to 2020

As you can tell, the Water Quality Standards, Assessment & Restoration (WQSAR) program at DEC is busy! We provide information and technical assistance to reduce water pollution; conduct water quality monitoring and watershed assessments; manage water quality information; and apply water quality standards in support of human health and the environment across Alaska.

Highlighted below are three upcoming activities the WQSAR program will be leading in 2020. If any are of interest to you or your organization, watch our webpages for updates or feel free sign up for one or more of our listservs to keep up to date on any notifications or announcements: Nonpoint Source listserv and the Water Quality Standards listserv.

Alaska Clean Water Actions (ACWA) grant solicitation

The ACWA grants program has a solicitation for projects every other year to allow for longer term or more complicated projects. Watch for an upcoming ACWA grant solicitation in the fall of 2020 for two year projects to start spring 2021 and run through spring 2023. View more information on the ACWA program.

Regional watershed assessments

Don’t be surprised if you see more WQSAR staff out at various streams this summer taking water quality measurements! We are initiating 2-year high priority watershed assessment projects on streams in the Juneau, Anchorage, Soldotna, Wasilla, and Fairbanks areas. We will measure core water quality indicators to characterize overall health and environmental condition. Final water quality information will be available from DEC.

Alaska’s Nonpoint Source Water Pollution Prevention and Restoration (NPS) Strategy

WQSAR is updating Alaska’s NPS Strategy, which outlines milestones and deliverables to accomplish for the next 5 years. The overall goal of the Strategy is to: Protect and restore Alaska’s water quality from the harmful effects of nonpoint source pollution. It balances protecting existing unpolluted, pristine or at-risk waters while also addressing impacted or polluted waters.

Although DEC is the lead agency for the state’s NPS Program, many other agencies, entities, and individuals have a part in the implementation of the NPS Strategy. Through communication, collaboration, and shared resources, Alaskans work together to effectively protect and restore water quality from the harmful effects of NPS pollution. The final approved NPS Strategy will be available on our website.

Alaska DEC WQSAR Staff Contact Information

As you can tell from this newsletter, we are a busy program accomplishing a variety of work. We invite you to get to know us better and the work we do every day in keeping Alaska’s waterways healthy .

These projects have been funded wholly or in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement 00J84604 to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use

Indicates an external site.

Indicates an external site.